DOCUMENTARIES

NOW IS THE FUTURE IN ORIGIN OF THE SPECIES

Director Abigail Child shows how far artificial intelligence has evolved.

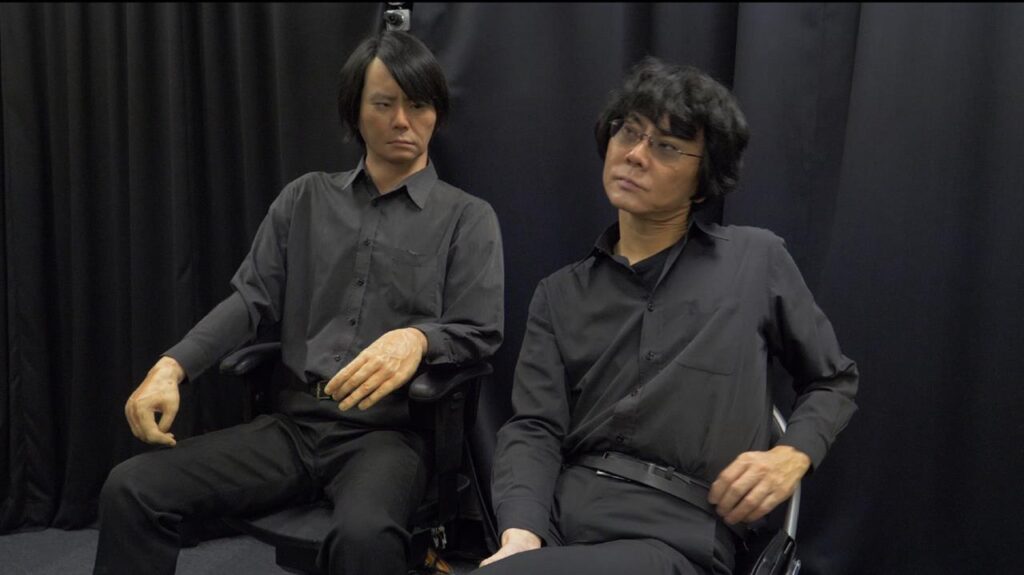

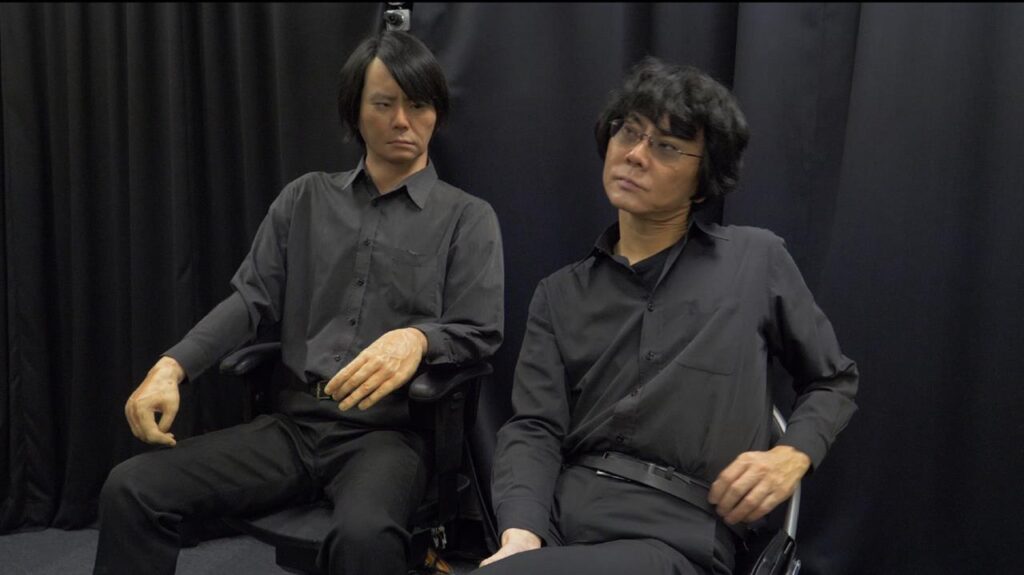

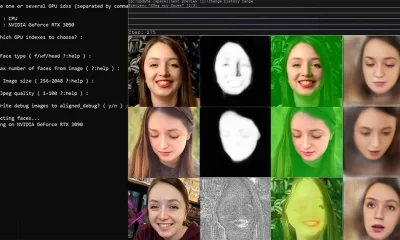

Ray Kurzweil spoke of the growth of technology being exponentially and we can see how this taking place as we speak despite a pandemic. When Elon Musk was speaking with Joe Rogan on his first-ever time on the podcast, he spoke of his concern about the growth of artificial intelligence and how there was no turning back. Joe Rogan also entertained the idea that they were both in a simulation and Elon Musk did not disagree at all. This brave new world of science, technology, artificial intelligence and robots can be quite overwhelming because like many other things it’s unprecedented and a journey into the unknown. Queer director Abigail Child takes this universe that breaks into many galaxies and worlds and combines into an artistic portrait. Set to make a screening at DOC NYC, Origin of the Species focuses on the human relationship with android development and the questions that are brought up when it comes to gender and ethics. Without getting lost in this universe, Abigail Child raises awareness of the rapid growth of artificial intelligence and humanity’s comprehension and position within it. FERNTV spoke to director Abigail Child about Origin of the Species and why this film is crucial to watch and necessary to explore.

FERNTV: Why did you call this documentary origin of the species which is very similar to Charles Darwin’s book title The Origin of Species?

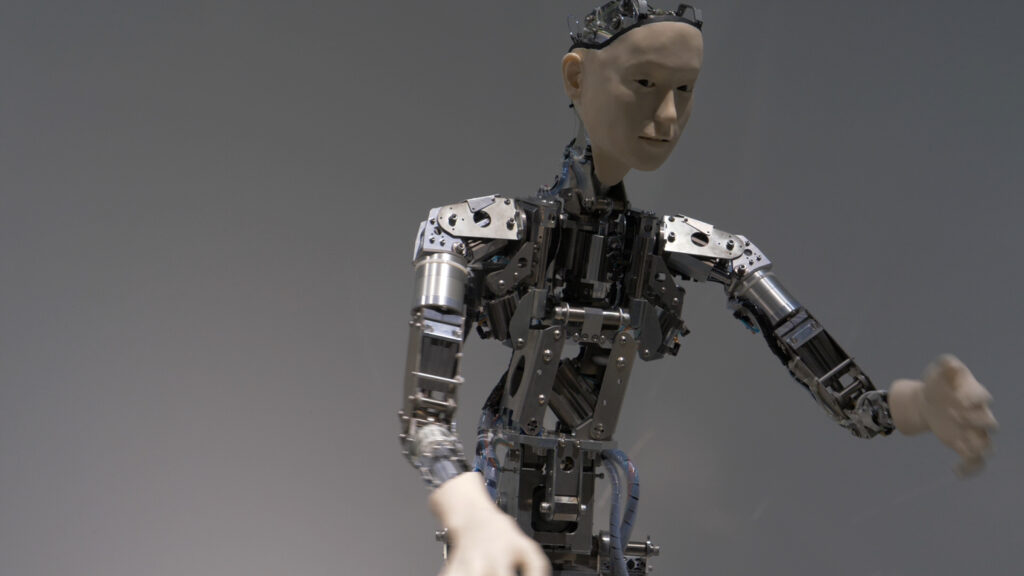

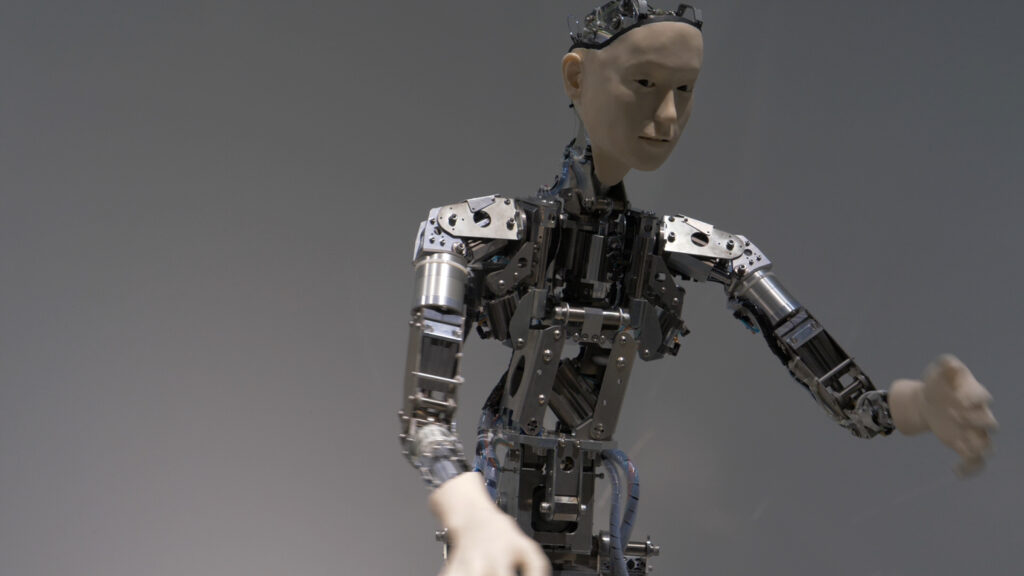

Abigail: I was fascinated that these robots were ‘evolving’, that scientists were developing them to move like humans, think like humans, speak like humans and have emotions. It seemed an enactment of the mythology, of the wish to create an artificial being (as in Frankenstein or with the medieval Golem). There is an aspect of playing at God, inventing a new “species”. The title captured that dual sense of both aspiration and scientific research.

FERNTV: What was your inspiration for doing this documentary? Do you have a fascination with robots or artificial intelligence?

Abigail: What could be more important right now than our relation to machines? We are already fully participant, while the final results on our society, our bodies, our minds,

remain unknown. AI decides what we watch on Netflix while algorithms on Facebook infect our politics. Data is drawn from us every minute we are on the web, walking

down the street, talking on the phone. There’s a big push right now to build increasingly sophisticated AI. With innovations in prosthetics and household units, AI

is already changing the way people live their lives. It’s easy to imagine a future where robots and people routinely live together in households. Sex robots are being built

and introduced into society; what will this do to human intimacy? This project places us close to the scientists who create these future machines. Some keep the human in the loop. Others create metal containers for bodies they feel are potentially replaceable: newscasters, receptionists, companions, sexual partners. The list is startling. Are we imagining that androids will inherit a world we poison? Is this contemporary research connected to our unconscious desire to populate a world that we have made hostile to human life?

This is the last of my Trilogy on Women and Desire, and the content has come full circle. The first film, Unbound, recreated the life of Mary Shelley, teenage

author of arguably the first sci-fi novel, in the form of imaginary home movies, shot in contemporary Rome. In the second film, Acts & Amp; Intermissions, I examine the life

of Emma Goldman and anarchism in the early 20th century where many of her struggles—for equality and immigration, contraception and against police

brutality—echo in the present. I knew I wanted a virtual woman for my 21 st century heroine.

My cultural influences include Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Philip K. Dick stories and automata such as the fortune-telling humanoid of the amusement arcades

at the Jersey Shore when I was growing up. Equally so, the cartoons I watched with obsessive affection. The result: an abiding interest in artificial construction, how it is

created and how our society will use/or enslave it.

FERNTV: Is there something about artificial intelligence that you still don’t understand even after doing this film?

Abigail: Oh yes! The numbers, the data compiled into strands of numbers that can create preferences, the full panoply of uses that algorithms can project. I understand the basics of statistics and some sense of logarithms, but I don’t code. I understand branching and hierarchies, choices where a computer can figure the steps and combinations quicker than a human mind, but how to enact those numbers? No. As an artist, you are always asking how more than why. You are also chasing what you don’t understand, trying to create new forms, new inventions. In that sense, we too are scientists, but their field is not mine. I have read molecular physics’ texts for inspiration, but I don’t have a scientific understanding. When I had the opportunity to attend a physics class at one conference, I could follow for about five minutes and then I was lost. Part of the appeal, of course, is to approach what we don’t understand, to try to stand under/beside/with— the unknown.

FERNTV: What are your thoughts on companies like Boston Dynamics?

Abigail: Mixed. They create amazing mobile robots. I find movement that imitates the human body more uncanny than when the machines “look” human. We are used to Wax Museums and dolls but to have something with arms and legs that can jump, push open a door and walk out into the world—is scary. Even without heads, these robots appear human and sometimes, threatening.

For a period, BD was under contract to DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) and indeed their robots were designed as war tools. However, because they are metal and mechanical, they are noisy—thus not fully adept for the battlefield. I was told that was why BD lost their contract. Here were oil-fueled machines, a lot noisier than cars! In one sequence I

show, the men working there had titled their piece “Boss Dynamics” which I thought, and they obviously agreed, says it all.

FERNTV: Elon Musk says that he is worried about the future of Artificial intelligence. What is your perspective on the future of artificial intelligence?

Abigail: Mattias Scheutz says in the last line of the film, that algorithms are learning from data without examining the results. He suggests human norms are necessary for extensive future robotic development. He is the moral compass of the film here, and I agree. I put some of his comments up against the Boston Dynamic enactment of the robot that “hits back.” Trying to

involve the audience in questioning what are human ethics? How can we encourage the development of AI into a humane track?

FERNTV: Who is your favourite robot when you’re growing up as a child and tell us why?

Abigail: I would have to say the fortune-telling humanoid of the amusement arcades at the Jersey Shore when I was growing up. She startled me. You would put in a quarter

and her eyes would light up and she would talk to you, tell you your fortune. Perhaps she didn’t even talk (am I remembering correctly?), just lights up and makes noises and releases a paper, like a fortune from a fortune cookie, emerging out the machine’s front! It was my first encounter with the uncanny as a body. I never forgot her. I loved the silliness of Robbie the Robot and Lost in Space, but that carnival humanoid machine had a three-dimensional reality that has remained powerfully in my brain.

FERNTV: What was the biggest challenge when making this film?

Abigail: Obtaining the first grant—from the Asian Cultural Council—which allowed for travel to Japan. We had begun to shoot at Tufts University’s Human-Robot Interaction

Lab in Massachusetts and knew we needed to go to Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka to get the full story. We were looking for money for over 2 years before we won that grant.

Very welcome. The other challenge—always—was the issue of how to structure the film. This involved many months of editing, trying various combinations of scenes, getting lost and finding the structure. The result usually ends up close to what you imagine at the beginning, but you don’t always know how to get there. You are not following a plan;

you are inventing a structure and have to figure out how to construct it.

FERNTV: What is the message that you want to relay to your viewers when they come to watch this film?

Abigail: I want my audience to question their own relation to machines and what the future may bring. How do we feel watching the current limits of the machines we keep

on improving? What does it teach us about being human? What do we make of a group of scientists engineering machines and algorithms to create a new life? And how

do different countries relate to these machines? How will our social experience change when interactive humanoid entities are as ubiquitous as smartphones? How will we respond to their humanoid, fashionable, possibly erotic, shapes? How will they lay into human emotions and instincts for bonding, for violence? How will androids

challenge our moral and ethical instincts? Will they make war in our place? Who will write their software personalities? Do they and AI really pose “our greatest existential

threat?” We want to bring these questions into public consciousness in a way that brings us face to face with this fundamentally disruptive technology.

As well, there is a mythical component. Robotics raises many issues of the artificial, the human, and the threshold between these, as well as the boundaries between the inanimate and the animate, the souled and the un-or non-soul, the present and the future, the real and imagination. These issues cross-cut into climate realities. As a young person, I sensed that rocks were alive, just slower than us. That instinct, or intuition, proved true when I learned of atomic particles. And we ourselves “come from stars.” I remember being incredibly startled, pleased, stunned really when I learned about the “redshift” and realized all the planets, the whole universe indeed was made of the same elements as on Earth. It was wondrous. It made us part of the universe, the earth as dear as our own bodies, sympathetic and synchronous. And that this wasn’t a frivolous assertion, but an ‘elemental’ and deeply, profoundly, ‘universal’ relation.

I add that the idea of a creature that might “imitate” a person has long existed in human myth and story, a constant dream. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein suggests

those desires and fears, as do earlier incarnations. Robots and androids, as well as implants and cyborgs, bring the future of an artificial human closer to reality. They suggest that the virtual is merging with the human, the simulation is spreading to the real. These developments reflect the future as present, as our dreams become engineered fact.

That the actual process—conception, manufacture and use—is often hidden makes the project that much more important and intriguing. Our aim: to promote thinking and a discussion that is timely, intelligent, humorous and cautionary.

www.originofthespeciesfilm.com

-

BIPOC4 months ago

BIPOC4 months agoThe Boy and the Heron @TIFF 2023

-

TIFF 20238 months ago

TIFF 20238 months agoViggo Mortensen in The Dead Don’t Hurt @TIFF2023

-

ACTORS/ACTRESSES2 months ago

ACTORS/ACTRESSES2 months agoAn Exciting Conversation with Sydney Sweeney @SXSW 2024

-

Uncategorized9 months ago

Uncategorized9 months agoWillem Dafoe in Gonzo Girl @TIFF 2023

-

ACTORS/ACTRESSES3 months ago

ACTORS/ACTRESSES3 months agoThe Exciting 96th Oscar Nominations Announced

-

TIFF 20238 months ago

TIFF 20238 months agoNicolas Cage in Dream Scenario @TIFF 2023

-

Uncategorized9 months ago

Uncategorized9 months agoSly to close TIFF2023

-

TRIBECA 202311 months ago

TRIBECA 202311 months agoMilli Vanilli @ Tribeca Film Festival 2023

Pingback: buy magic mushrooms online